By EMMANUEL ARODOVWE

March 14, 2025 made it exactly one year to the day in which the little known community of Okuama in Urhobo land was suddenly shot to global consciousness over the strange death of 17 Nigerian soldiers who had controversially left their places of primary postings, to engage in what was later described as a peace mission, over an alleged land dispute between Okuama community of Urhobo and neighbouring Okoloba community of Ijaw. Casualties on the civilian side of the deadly confrontation was conspicuously underreported if not outrightly overlooked.

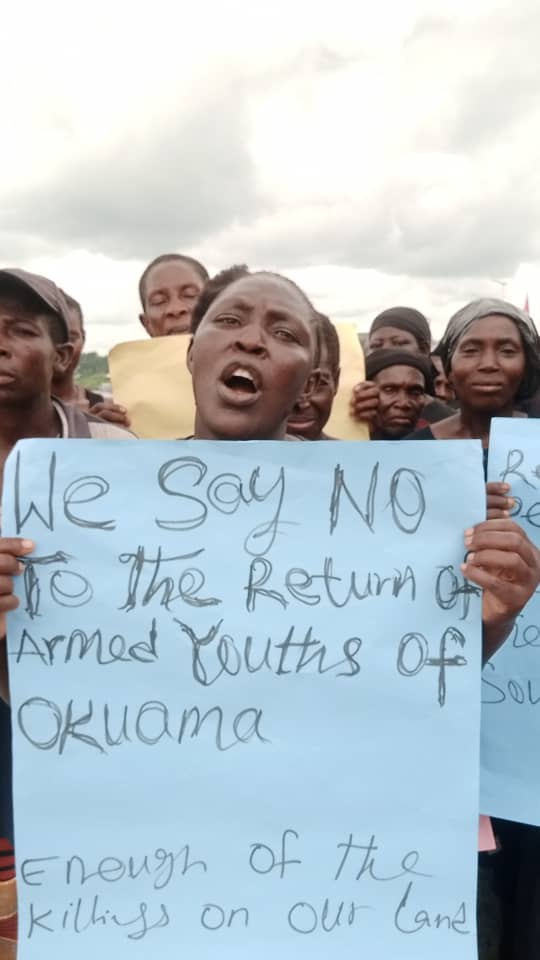

Within seven days of the incident, the army authorities in a retaliatory move unleashed mayhem on the community, with the elderly and children finding covers in bushes and thick forests, where many of them either starved to death or were killed by wild reptiles.

What followed was a levelling of the community such that no building, school or any other public facility was left standing except an Anglican Church established by the legendary Bishop Agori Iwe in the mid-20th century. One year after, that church building has remained the only mustering point and living quarters for hundreds of lucky survivors of that incident.

The Federal Government through President Bola Ahmed Tinubu commendably conducted an elaborate state funeral for its fallen officers, eulogising them for their courage, and promising to get to the root of the very controversial engagement and ensure that justice was done. The army thereafter arbitrarily declared persons they imagined to be suspects wanted. They included the king of Ewu Kingdom HRM Clement Ikolo and the President General, Professor Arthur Ekpokpo.

These publicly declared persons were taken into custody of the army at different times and have remained with them one year after. It took the intervention of some highly placed people in the society to effect the release of the king after about a month. The professor and many others have remained in custody till date. The inhumane torturous condition in which they now live, which include no access to phones, sleeping on bare floor over mosquito bites and starvation, is simply despicable. One of the victims of this arbitrary arrest, an octogenarian, unwilling or unable to manage the ordeal any further, died some months ago. Another elderly victim was on the verge of giving up the ghost when his frail body was released by his captors, as if to say to his people: “take away your dead for burial”. Somewhat, the old man has managed to survive but with his sanity now lost for ever.

But what is more troubling one year after is that the Okuama community has remained levelled and abandoned, without any serious commitment from the federal and state governments to rebuild and resettle the people. The Internally Displaced Persons, IDPs, Camp set up by the state government as an immediate temporary response to the crisis has now been shut, leaving the people stranded. As it stands, a generation of Okuama children are now denied the right to education, having missed an academic year out of school with no hope in sight of resumption any time soon. Households have been callously torn to shreds as a result of this incident, and livelihoods are presently non-existent.

The Okuama incident one year after, forces afresh two different but related issues that border on justice and the fate of the minority in the amalgamated Nigerian state.

The matter of justice and fairness in Okuama

A major question arising from the Okuama incident is the identity of the commanding officer who ordered the intervention of the Nigerian Army officers over the community dispute and what factors necessitated that very extreme option. Every society, no matter how disorderly, has at the very least, designated roles and duties for different institutions and their personnel. It is not the duty of the army, anywhere in the world, Nigeria inclusive, to be the first point of call in a strictly civil matter, in which no gun has been shot, and not even a single case of physical combat has been recorded. To mobilise such an army of soldiers over a matter that even the local police were not yet aware of, raises suspicions that must be investigated thoroughly. One year after, despite promises by the president, no effort has been made to identify exactly what mission it was the officers went for, and on whose order.

It requires a matter of serious security threat bordering on territorial risk, for troops operating in locations far and disconnected from each other, to be rallied, to engage defenceless citizens with live ammunition.

There is another point that begs for clarification. Why was the choice of location to keep the peace on the Okuama side of the divide rather than on the Okoloba side? Why was a neutral venue not chosen where the parties are invited to state their case and a peace treaty signed at the end of all deliberations? Why indeed did the military, having controversially intervened in a civil matter, not immediately report to the police who are better fitted to examine such cases?

The lesson from global history is that the host territory of any combative engagement bears the brunt of the devastation resulting from that incident. The Seven Years War in Europe (1756-1763) was fought largely on German territory, although the combatants were Britain and France over who owns where in North America. It set Germany backwards for centuries. The World Wars were fought on European territory and they set Europe backwards for decades.

The choice of Okuama rather than Okoloba as the location for a military fierce engagement using live ammunitions has now given an unfair advantage to Okoloba in this crisis. No Okoloba citizen suffered any harm; no facility or building were levelled in Okoloba; no livelihoods were lost in Okoloba. Yet, Okoloba is an implicated party in the dispute. This forces a suspicion that the military, whether through inducements or ethnic considerations, had taken sides and were simply used as mercenaries to implement the biddings of the other party in the dispute.

There is another point of concern. It relates to the objective of the unjust incarceration of the Okuama citizens under inhumane conditions by the army, and how long hereafter they still have to remain unattended in their ordeal. When will they be charged to court to state their side of the story and prove their innocence? When will their fundamental human rights to fair hearing be recognised?

The fate of the Minority in the Nigerian state

The Okuama incident has also reawakened afresh the concerns of minority groups as it relates to their status and destiny in the Nigerian amalgam. This minority fears is not new. As far back as 1957, such concerns have been expressed, and necessitated the setting up of the Henry Willinks Commission to look into them. The Commission admitted existing cases of neglect, injustice and oppression in the Niger Delta region, which also extended to a cluster of ethnic nationalities in the Igbo-dominated Eastern Region.

What those early agitators could not forsee was a worse future, marked by the discovery of crude oil in their region, and a Decree 34 of 1966, which would annex all these assets to properties of the central government, with the people reduced to conquered tenants. It implied that the Niger Delta peoples became economic burden bearers of the Nigerian state, the perpetuation of which would require a culture.of plunder and exploitation, to be overseen by gun-wielding military officers.

It is the attraction of this “liquid gold” and the resolute determination to maximally exploit it for Nigeria’s benefits that have informed the over- militarisation of the Niger Delta and the callousness with which the natives are treated. The Okuama incident one year after, if anything at all, has brought back the sad reality of the pariah status of citizens of the Niger Delta in the Nigerian state; that far from being citizens, the people’s of the Niger Delta only constitute statistics that exist in a territory of economic interest to Nigeria, and are thus obstructions or impediments on the economic pathways of the country.

Consequently, they could, or indeed, deserve to be brutalised, abused, maimed, locked up, indeed killed, as long as it clears the path for Nigeria’s petro dollar income. That the human has an inalienable right and intrinsic worth and dignity bestowed by God matters little to the Nigerian government in its engagement with the Niger Delta peoples. The Okuama incident, if its remotest causes are to be excavated, would be seen that it is “all for oil”.

There is even a more consequential point that the Okuama incident impresses on the mind. It raises the question of the propriety or otherwise of maintaining an amalgam, created by a colonial officer over a hundred years thereafter, especially in the face of numerous evidence that “the union is not working”.

Frederick Lugard took the pragmatic step to amalgamate Nigeria because he thought it made more economic sense to the British to administer the two colonies as one, so that the excess earnings from the South could augment the deficit in the North. He also thought that since the North was landlocked, goods that had arrived in the South could easily be moved to the North without hurdles. He also thought that the more educated citizens of the South could join the civil service in the North for cheaper pay than maintaining British personnel who were eager to return home. That pragmatic move by Lugard saved the British five hundred thousand pounds annually as imperial grant in aid which they had paid consistently in the past 10 years.

Lugard did not set out to establish a nation when he amalgamated Nigeria, because he knew that it was impossible, given the cultural, historical, religious and social differences. He only desired a colony that he could administer easily without recourse to London for aid.

Over hundred years after Lugard, there is now sufficient evidence that what was true for his age and time has now been overidden by more pressing issues of justice, fairness, self-determination, liberation, and nation state actualisation.

Several instances abound in world history where a collection of nationalities, once amalgamated for administrative convenience, outlived that objective, and thereafter set themselves apart to live their lives undisturbed and uninhibited. The USSR, Yugoslavia, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire are easy cases in point.

The Okuama incident, one year after, forces a reflection on self-determination, right to independent statehood, the cultural nation state, etc. All these are rights captured in the 1948 United Nations Declaration of Human Rights that were part of the outcome of the Second World War. The standard practice in Europe of the 21st century is that people of one language and socio-historical evolution should exist as an independent country of their own – it doesn’t matter if they are as little as fifty thousand like Andorra or as large as sixty million like France.

There is now the feeling since the Okuama incident that the pessimism expressed by some of the founding fathers of Nigeria were not misplaced afterall. Nigeria’s first Prime Minister Alhaji Tafawa Balewa noted that “God did not create Nigeria, the British did”, and second, “there is nothing sacrosanct about Nigeria’s unity”. Chief Awolowo was even more categorical: “Nigeria is a mere geographical expression”.

There are many things that the human cannot change about his or her life. Philosophers call them facticities of human existence. They include one’s parent’s and family of birth, one’s linguistic origin and identity. One of the facticities of human existence is definitely not the amalgamated state to which one is compelled to identify with. That certainly is changeable. What amalgamated societies do to placate their population and prolong their existence is concerted effort at promoting happiness and peace among them. They seek the welfare and development of their country so much that the people take the issue of self-determination as less important. A case in point is Switzerland with four national groups but with ample space enough to live their individual national lives uninhibited, that they do not imagine leaving the union any soon, even though they reserve the right to, and can demand it at any time. But where an amalgam abuses its privilege of existence by trampling on its population, abusing their rights and killing them at will, it is only hastening its demise.

Urhobo nation, just as many ethnic nationalities all over Nigeria, existed for about 2000 years or more as a distinct socio historical group, engaging in trade and diplomatic relations with others, long before Nigeria was born. Nigeria is a recent phenomenon in comparison to the authentic nation states and peoples she now arrogantly abuses. Urhobo, just as all nations chained to the Nigerian project, will exist viably, if and when, they exit Nigeria.

Incidences like Okuama depicts the pride of an amalgam on its way to perdition. It is therefore a timely instruction to the managers of the Nigerian state to seek and pursue justice in the interest of the collective coexistence of all. The Okuama incident one year after, epitomises the moral decay, the injustice, the abuse of human rights, the corruption and high-handedness by which the Nigerian state is now notoriously famous both locally and internationally.

•Arodovwe, an activist, wrote from Okuama, Delta State via: [email protected]

The post Unanswered questions from Okuama: One year after appeared first on Vanguard News.